While Americans were distracted [as usual] over the holiday season, something extraordinary happened: China launched its first power projection mission in over 500 years by sending a small naval flotilla of two destroyers (DDG-171 Haikou, DDG-169 Wuhan) and a supply ship (Weishanhu)to conduct counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden. With its own shipping industry vulnerable to pirates, China has as legitimate an interest in the Gulf of Aden as any other seafaring state, but this deployment signals something much more significant.

China is increasingly reliant on raw materials imported from the Middle East and Africa to fuel its economy. This is a major security vulnerability because this relies on very long and very vulnerable sea lines of communication (SLOCs) that cross the Indian Ocean and transit the Strait of Malacca before reaching the Chinese coast. As discussed in an earlier post, China must import most of its oil along these SLOCs, and though it is establishing a number of overland pipelines to reduce this problem, it will still be dependent on oil carried over the ocean; severing China’s SLOCs would bring the Chinese economy to a standstill in a matter of days.

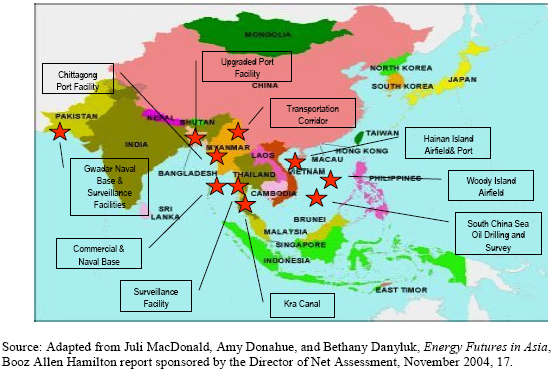

Maintaining its shipping lanes is therefore a national security imperative for Beijing. In addition to building up a formidable navy, China has been subtly establishing centers of influence along its SLOCs, from the South China Sea all the way to Sudan. US analysts call this the “string of pearls” strategy, each “pearl” being a nexus of Chinese influence that it could eventually utilize toward the SLOC security mission. In the South China Sea, where the “pearls” are located on Chinese territory and small islands Beijing has laid claim to, they have a blatant military character with airbases and port facilities to support military operations. West of the Strait of Malacca, however, they are much more subtle and often take the form of Chinese-funded harbor upgrades.

China's String of Pearls

With the deployment to Somalia, China is finally activating the “string of pearls,” selecting the perfect opportunity to do so: the enemy is pathetically weak and hated by every state with a shipping industry, and the operation has the blessing of the UN Security Council. China is threatened by pirates just like every other oceangoing power, but it certainly did not have such petty threats in mind when it crafted it maritime security strategy. The Chinese navy and the “string of pearls” are directed against other naval powers (primarily the US), the only threats capable of completely severing the SLOCs. Piracy offers a convenient pretext to begin staffing the “pearls” with a permanent military presence, enabling Beijing to project power throughout the Indian Ocean. From this day forth, the Gulf of Aden and the western Indian Ocean will be a permanent duty station for the Chinese navy, with one or more warships constantly patrolling in the region. The Pakistani port of Gwadar – having been upgraded with Chinese funds – will be an adequate base for the flotilla. China could establish some form of presence in Yemen, adding another “pearl” to its network.

The same strategy could be used to establish a permanent military presence in the Andaman Sea near the Strait of Malacca; this region also suffers from piracy, and the next spike in incidents could prompt China to dispatch another flotilla. Myanmar – which has been cultivated as a client regime by Beijing – would be more than willing to provide bases on its coast.

The historical significance of this mission deserves to be recognized, but we should not lose sight of the fact that it is part of a wider Chinese strategy that only incidentally overlaps with the counter-piracy mission. The world would do well to recognize this strategy for what it is, because it will be dealing with it for a very long time to come.