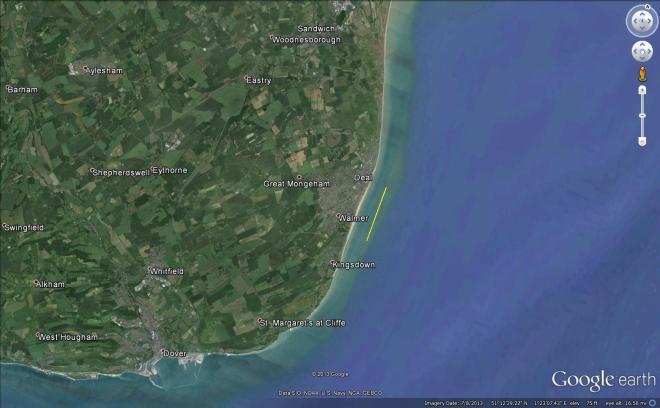

In 55 BC, after several jolly years of massacring various Gallic and Germanic tribes, Julius Caesar found himself along Gaul’s Channel coast and within range of a tempting and lucrative target: Britain. The conquest of such a distant and reputedly wealthy island would bring great glory to Caesar, and thus he prepared a small amphibious expedition of about 2 legions (VII and X) to reconnoiter Britain in preparation for a larger invasion in the future. Caesar’s own narrative of this campaign describes one of the earliest amphibious assaults in history, in that the landing had to overcome opposition on the beach itself:

The natives, on realizing his intention, had sent forward their cavalry and a number of the chariots which they are accustomed to use in warfare; the rest of their troops followed close behind and were ready to oppose the landing. The Romans were faced with very grave difficulties. The size of the ships made it impossible to run them aground except in fairly deep water; and soldiers, unfamiliar with the ground, with their hands full, and weighed down by the heavy burden of their arms, had at the same time to jump down from the ships, get a footing in the waves, and fight the enemy, who, standing on dry land or advancing only a short way into the water, fought with all their limbs unencumbered and on perfectly familiar ground, boldly hurling javelin and galloping their horses, which were trained to this kind of work. These perils frightened our soldiers, who were quite unaccustomed to battles of this kind, with the result that they did not show the same alacrity and enthusiasm as they usually did in battles on dry land.

This imagery reminds me of Omaha Beach, with heavily laden U.S. soldiers having to wade under fire through 200 yards of neck-deep water before because the landing craft dropped their ramps too far offshore.

Caesar also describes how he used warships as fire support platforms to cover the infantry trying to fight their way ashore:

Seeing this, Caesar ordered the warships – which were swifter and easier to handle than the transports, and likely to impress the natives more by their unfamiliar appearance – to be removed a short distance from the others and then to be rowed hard and run ashore on the enemy’s right flank, from which position slings, bows, and artillery could be used by men on deck to drive them back. This maneuver was highly successful. Scared by the strange shape of the warships, the motion of the oars, and the unfamiliar machines, the natives halted and then retreated a little.

With the infantry struggling to capture a beachhead in the face of determined opposition, Caesar ordered some of his reserves from the transports onto more maneuverable vessels that could rapidly exploit weaknesses in the enemy’s defensive line. This ultimately won the day for Caesar.

Both sides fought hard. But as the Romans could not keep their ranks or get a firm foothold or follow their proper standards, and men from different ships fell in under the first standard they came across, great confusion resulted. The enemy knew all the shallows, and when they saw from the beach small parties of soldiers disembarking one by one, they galloped up and attacked them at a disadvantage, surrounding them with superior numbers, while others would throw javelins at the right flank of a whole group. Caesar therefore ordered the warships’ boats and the scouting vessels to be loaded with troops, so that he could send help to any point where he saw the men in difficulties. As soon as the soldiers has got a footing on the beach and had waited for all their comrades to join them, they charged the enemy and put them to flight, but could not pursue very far, because the cavalry had not been able to hold their course and make the island.

What I find remarkable is the extent to which this operation, over 2,000 years ago, presaged the fundamentals of modern amphibious warfare – including mobile offshore fire support, the abandonment of failed lodgements and the exploitation of successful beachheads with waves of reserve infantry – albeit on a reduced scale.

Caesar would return to the continent not long after. He again invaded Britain in 54 BC with a much larger force and this landing was unopposed. However, Britain turned out to be much less wealthy than Caesar had thought, and garrisoning the island was far more trouble than it was worth. Again Caesar returned to the mainland to deal with restless tribes. Rome would not return to Britain for another century.